|

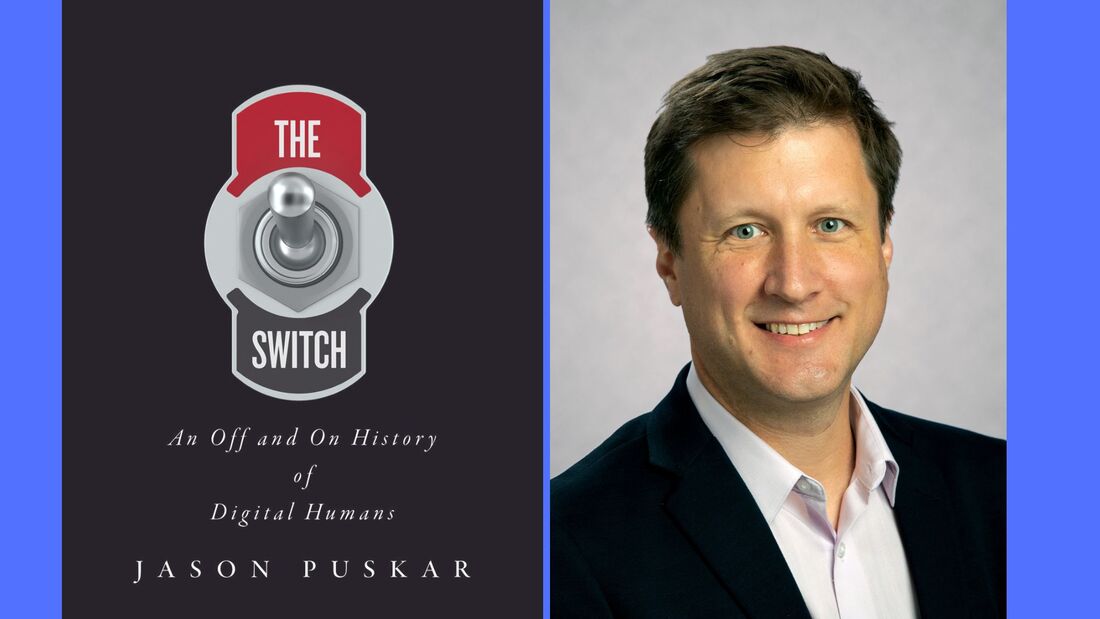

By Tea Krulos Professor Jason Puskar of University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee has been a great friend of QWERTYFEST MKE and QWERTY Quarterly. He gave a presentation at last year's QF on the history of the QWERTY keyboard and Christopher Latham Sholes, the Milwaukeean who configured it. In our last issue of QQ (#2), Puskar analyzed a letter typed by Sholes in 1869 on a typewriter prototype and he’s been helpful in brainstorming and making connections. We’re thrilled to talk with Puskar about his new book, The Switch: An On and Off History of Digital Humans. This fascinating book delves into technology from telegraphs to touchscreens– technology we don’t really think much about, but that we use constantly in everyday life. QQ: What started you on the path of researching switches and buttons? I think it was probably having kids, and watching their strange attraction to switches and buttons. They would have murdered each other to be the first one to push the elevator button, but when you think about it, just pushing a button or flipping a switch is not really a very interesting activity. It’s undramatic, and the same thing happens every time. But it was clear that it meant something important to kids, and I wondered if it meant something important to adults too. And I think it does. When a child pushes the button to summon an elevator, it’s true that not much happens right away, but they understand that after a few seconds they have somehow summoned a magic room that can transport them to completely different places. Now that’s something! And if you think about children and what they can do—well, they can’t do much. They can’t drive, cook, they’re uncoordinated, their drawings basically all suck (let’s be real here), and the few things they can do well, like destroy stuff, we forbid them to do. And anything they try to do takes huge effort too, so it’s all very hard work for them, with very low returns. Then suddenly here’s this magic room that they can summon instantly, with no effort, and transport the whole family elsewhere! What kid wouldn’t want to experience that little jolt of mastery and power? And in the long run, I eventually thought, what adult wouldn’t want that too. QQ: The QWERTY layout happened so long ago-- why do we continue to use it in this digital age? It’s like the four-foot tall front wheel on a tall Victorian bike, except that in this case we’re still using it. There are undoubtedly better ways, but even though we figured that out with bicycles we never quite did with keyboards. There’s always a temptation to talk about keyboards in utilitarian terms, as if we had no choice to use the most efficient option. But why should that be the case? We don’t do that with fashion, after all. Why do men wear neck ties? It makes no sense from any practical perspective, but we do it because our fathers did it, and their fathers did it, and their fathers did it. It became part of our culture, so we keep transmitting it forward. Or women’s high heels are another example. This is the worst possible shoe a person could imagine, but for some reason we decided we liked them, so we keep using them. Or wine glasses with tall stems. We’d be much better off without them! I think QWERTY is really part of this world of aesthetic expression, and not really a utilitarian machine destined to find its most efficient form. I love the irony that aesthetic forms are the most changeable of all—they never have to be any particular way—but like ties or wine glasses, somehow the non-utilitarian nature of the form is exactly what ensures that it stays. QQ: Other than the QWERTY, what have you found to be some major milestone key, lever, switch developments? It’s hard to identify a first switch, but the Morse telegraph key is close. But even before that there were two really crucial sources that are something like the great, great, great (and so on) grandparents of all of our switches: gun triggers and musical keys. Gun triggers—and crossbow triggers even before that—are also binary, in that they release stored energy in an all-or-nothing way, all at once, and with the touch of a finger. Early organ keys dating back to classical Greece are similar: they retrieve a pre-programmed musical note from the full array of possible pitches, instantly and with no groping for precisely the right pitch. So guns and organs—these are the violent father and artsy mother of many of the switches we know today. And you can still see the family resemblance. In photography, we press a shutter button and “shoot” a photograph, or “trigger” a flash, and many early cameras were shaped like guns. The first wireless TV remote control was shaped like a pistol, and you had to aim and fire it at the set. The organ, on the other hand, influenced the keyboards we use today, and in fact most nineteenth-century writing machines before the Type-Writer had some sort of musical keyboard for an interface. As for other milestones, electrification allowed for huge leaps in automation and ease of operation. So did the virtual buttons that started appearing on Graphical User Interfaces in the 1980s and 1990s. But mostly what impresses me is the wide range of applications of switches throughout the twentieth century, especially. QQ: We think of technology development as being good, but did you encounter cases where that might be questionable? A lot of it is really regrettable, actually. This book is not a love story for the switch, I’m sorry to say, though switching does have many beneficial functions too. On balance, though, I think switches fuel fantasies of mastery and domination in the people who use them, because they start to take for granted the apparent extent of their own power. I also think they’re hyper-individualizing, in that they make it seem like action is less an interactive process involving lots of different people and things, and more like a single result coupled to a single person who compels it. So in that way, switches are ideological or political, because they shape our consciousness of how people are, and how they should be. They’re little engines of individualist doctrine, by helping us take our apparent but not actual independence for granted. After all, we’re dependent on switches to feel independent a lot of the time. QQ: Can you tell us a takeaway you hope people get from the book? Our technologies act back upon us, shaping our conceptions of ourselves so profoundly that they even help define what it means to be human. For example, I wear glasses, have a mouth full of dental fillings, and a knee held together by titanium screws. Without these mechanical aids, I couldn’t read, wouldn’t have many teeth for chewing, and would struggle to get around on my own two feet. But with them, I feel great, and as long as I forget that I’m dependent on these mechanical helpers I feel really independent, strong, and capable. My point is that switches do something similar for us, but even more invisibly than the prosthetics that make me into an able-bodied human. They’re like mirrors that reflect back an image of ourselves at twice our actual size. So even though we think switches just sit there passively, waiting for our touch, they’re always acting back upon us too. The Switch: An On and Off History of Digital Humans was published in November 2023 by University of Minnesota Press, www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/the-switch The article appeared in QWERTY Quarterly #3. Check out our QQ #4 release party:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

QWERTY

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed